I created Living ROI as a passion, to share my experiences and support others who want to live more authentic, joyful and fulfilling lives.

Dear Friends,

For Mother’s Day, I asked my daughter, Emerald, to share an extraordinary experience she had Wednesday night in New York on her way home from work.

“On Wednesday I didn’t leave work until 8 PM, and I had a lot on my mind. I was anxious about a presentation happening the next day, running through the PowerPoint slides I had been preparing over the past three weeks, trying to remember if I missed anything.

I walked from my office to Penn Station to catch the subway home, hoping I wouldn’t have to wait too long for the train. As I speed-walked through crowded Midtown, every person who jostled me or who was walking at what I deemed a slow pace, annoyed me. I was in a rush, I was trying to get home, and I was hyper-focused on ME.

I got into Penn Station, jogged down the stairs to the underpass to get to the downtown track, and I saw a man lying on the floor. He was clearly homeless, dressed in dirty clothes and sneakers, and the whole tunnel smelled like someone who hadn’t showered in weeks. Walking around New York, you see homeless people sleeping all over the place, and I walk by them every day without batting an eye.

But this man was not sleeping. He looked like he had just fallen; both his hands were on the ground, and one of his shoes had fallen off. He did not look okay. As he came into my view, I saw him lose consciousness and watched his head and chest slowly sink to the ground. Honestly, I thought I had just seen him die.

I walked past him to the stairs that lead up to my train platform, looking at him the whole way to see if he moved. He did not; so I circled back, looking around as I went to see if any of the other commuters saw what I had just seen!

I walked past him a few times; it didn’t feel right to leave him there. I went back up to the subway entrance where there is sometimes an MTA employee sitting in an information booth. There was no such booth at this station entrance, so I went back down. Several people were walking past, and I sort of tried to ask one of them for a second opinion on the situation, but they all had headphones in, or were on the phone, and honestly, and unfortunately, I felt like I would be bothering them. I felt like this homeless man’s life was not an important enough reason to tap someone’s shoulder and interrupt their podcast.

I went over and squatted down next to him, and I felt awkward and embarrassed. Embarrassed to be getting so close to this man who every other person in the station was walking past. A man who smelled so bad that every other person who entered the underpass wrinkled their noses. I felt embarrassed to be caring.

But I touched him anyway. I touched his arm and asked him if he was okay; no response, so I shook him a little more forcefully and asked him again and still no response. I tried to feel his pulse on his wrist, but I’m not a nurse, and I’ve never even been able to find my own pulse on my wrist, so I ditched that idea. I put my fingers under his nose, and I felt that he was breathing. Thank God, he’s alive.

As these thoughts rushed through my head, I realized that there was a protocol set up for a situation exactly like this one, and I called 9-1-1. What better second opinion to get than a medical professional’s? The operator picked up immediately, and when she asked, ‘What’s your emergency?’ The first words out of my mouth were, ‘There is a homeless man unconscious at the 34th Street subway station and he is unresponsive.’ It felt necessary to qualify that he was homeless because I still felt embarrassed. I felt like I was wildly overreacting to a situation that dozens of other New Yorkers were witnessing and walking right past.

While I was speaking with the paramedic on the phone, another commuter came over to us. He asked, ‘Is he breathing?’ I said yes and that I was on the phone with 9-1-1. This man turned out to be an Army Medic, and he checked the unconscious man’s pulse. ‘Probably an overdose,’ he said, matter-of-factly. I nodded and told him how I had seen the man crumple to the ground earlier.

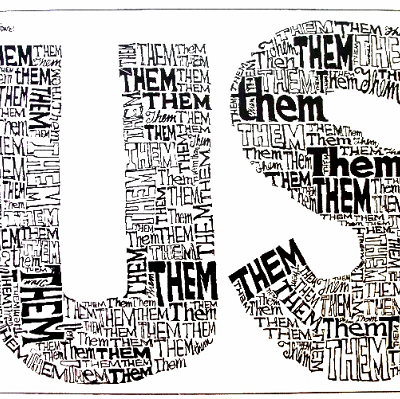

I realized that my earlier embarrassment was coming from thinking I was being naive. Maybe this happens all the time and I just didn’t have enough information. Enough information to recognize an OD and just keep moving; because who cares about another street urchin who’s wasting away on drugs?

This Army Medic quickly relieved my fears. He said, ‘It’s good you called 9-1-1,’ and he couldn’t believe how many other people were just walking past. ‘When we lose our humanity, what do we have left?’

The EMT arrived, flipped the man over, took his vitals and sprang into action. They were ripping wrappers off syringes, propping his mouth open, manually pumping oxygen into his lungs and giving him an IV. The Army Medic and I stood back and watched them work, and I noticed that NOW everyone else was also stopping. Not to help, but to watch. Is it because the presence of medical professionals verifies that this is a serious situation? Is it the rubberneck phenomenon? I don’t know the answer.

When the man sat up and started breathing, I felt so relieved. It was a heroin overdose, the EMT verified. I thought, ‘This is the opioid epidemic, right here.’ And now what? Does this man just go back to living on the streets of New York City, still a heroin addict?

The Army Medic and I shook hands, exchanged cards, and he carried on his way. I stayed for a minute longer, the EMT asked if I was also a doctor. I said no, I had just called 9-1-1 because this man did not seem okay. ‘It’s good you called us’, he said, ‘You saved his life.’

As I turned and walked up to my train platform, I felt like he gave me way too much credit. The EMT and his partner saved his life! I had just stopped and dialed a 3-digit number. But as I told this story to more people, and talked about the experience, I realized that calling 9-1-1 took a lot of effort in this situation.

I reflected on how many people walked past while I hung around and checked his breathing, how many people walked past while I was on the phone with the EMT, and how many continued to walk past while he was being resuscitated. People walked past a man who was dying on the floor in front of them. At what point did this become the norm? When did catching a train become more important than another human life?”

As a mother, of course I’m proud of the action Emerald took. As a citizen of this world, I am sad and feel helpless about the growing problem of addiction and homelessness all around us. We seem to be numb to it, and the solution seems nowhere in sight.

I am reminded of one of my favorite quotes:

If you can’t save everyone, just take care of what is right in front of you. Thank you for the reminder, Emerald!

Love to all,

Barbara Fagan-Smith

CEO, ROI Communication

Chief Catalyst, Living ROI