I created Living ROI as a passion, to share my experiences and support others who want to live more authentic, joyful and fulfilling lives.

Dear Friends,

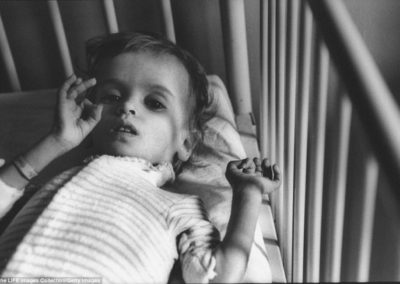

I remember the day The First Gulf War, Operation Desert Storm, started. It was a freezing morning in January of 1991, and I was in Constanza, Romania on the Black Sea. My hotel room had a broken window and I had stuffed a towel in it to stop the cold wind. At the time, I was covering a story on AIDS babies in orphanages in Romania—discovered after the fall of the dictatorship of Nicolae Ceausescu just a month before. I was listening to BBC News on a 4 Band portable radio and heard the announcement of the air attacks on Iraq and Kuwait.

Seeing these young Romanian children, many of whom had hardly been held nor given any stimulation or socialization, was indescribably sad.

Just a few weeks before the war started, I was on an international flight sitting next to a lovely young woman from Iraq. She told me how nervous everyone was in Iraq about a potential war. I wondered what impact the war would have on her and her family.

A few months later, in March of 1991, the First Gulf War was officially over. My boyfriend, a cameraman for ABC News, and I were taking a much-needed vacation on the Turkish Riviera when I was called by ABC to get to a remote region on the Turkish-Iraqi border ASAP. The Kurdish Refugee Crisis was just unfolding on the border, and it was very difficult to get anyone to the region. The news bosses at ABC in the New York headquarters were thrilled we were already so nearby.

Barbara in a hotel on the Turkish Riviera, but not for long!

I was a field producer for ABC News based in London, and as it turned out, had just been to this remote region a couple months earlier while covering Iraqi soldiers who had deserted the army during the war by crossing the border into Turkey.

Getting video footage of Eastern Turkey on our way to the border during the war. ABC correspondent interviewing Iraqi deserters.

It’s hard to get to this region of Turkey in the best of times, but at that moment the Turkish airline was on strike. We ended up chartering a flight with two BBC journalists to Diyarbakir, Turkey, and then drove through the mountains for hours to the small border village of Ortasu.

What we found was a disaster.

Thousands of Iraqi Kurds had fled the northern towns of Iraq after Saddam Hussein began to attack. Once the war ended, the Iraqi Kurds had rebelled in hopes of carving out their own sovereign state. After failing to receive support from the U.S., thousands of Kurdish families fled for their lives. These were city people, coming from Mozul, Erbil and Kirkuk, with little more than the shirts on their backs—no food, no provisions, nothing.

The only support on the ground was the Turkish army. It took the Red Cross and Doctors Without Borders another four days to get there. Two reporters from the BBC, my boyfriend and I were the only journalists, and the only Westerners, present. The BBC had a mobile satellite dish, so we were able to broadcast audio news reports for the first week.

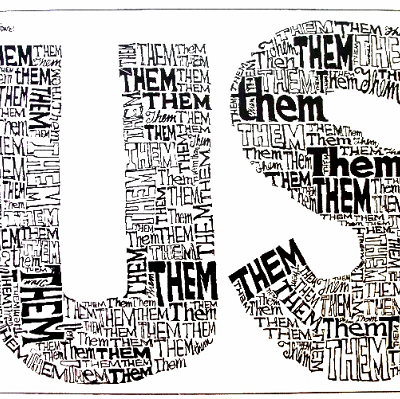

As I took my first walk into the makeshift refugee camp, I was immediately surrounded by dozens of people, begging me to help them. One woman grabbed my leg and said, “Please help us! We are Christian.” It did not matter what religion they were. I wanted to help them all. And I couldn’t. Not only because our supplies were scant, and the Turkish military refused to allow any of the refugees into Turkey, but also because of the code of journalism. I wasn’t supposed to cross the line and interfere with the news—just report it.

A few days later, after Doctors Without Borders had arrived, a young man came to me in the middle of the camp with his sick baby in his arms and begged me to help him. I pointed to the Doctors Without Borders tent, and he went there. Fifteen minutes later, he walked by again, with his dead child in his arms. That memory came storming back when I held my own child in my arms for the first time.

The U.S. Military started dropping food bundles and supplies from planes right at the border, on and around land mines. The young Iraqi boys and even older men ran to get the supplies, and every now and then they would get a leg blown off. Any injury that one might survive with available medical care and sanitary conditions was deadly in this festering, septic, disease-infested environment. By now, the mosque, a makeshift morgue, was filling up quickly with those who had no breath for prayers.

One day I was in the makeshift “hospital” watching a man with half his leg blown off moaning and moaning. Without water or supplies, all the Turkish military could do was put a tourniquet on what was left of his leg and hope he hadn’t lost too much blood. But they really weren’t too concerned. He was an Iraqi Kurd and wasn’t welcome in Turkey dead or alive. This was before Doctors Without Borders had arrived. I was just a few feet away as this man took his last breath. The makeshift gurney brushed my leg as they carried him to the mosque.

I walked back to our shack to have dinner and realized, as I relayed the story to my journalism colleagues, that I had no emotion about this situation. I mentioned that fact, and the other three veteran journalists said, “Of course not. If you felt this stuff, you couldn’t do this job. You have to turn it off. But the strange thing is, once it’s off, it’s hard to turn back on.” At that moment, I told myself I wouldn’t let that happen to me. I couldn’t let that happen to me. I wanted to feel it all, and after this experience, if I got out, I would make a change.

Our sleeping quarters with another reporter and the kitchen with a Turkish helper.

After two weeks on the border, I got a severe intestinal bug that had me laid up for a full three days. As I lay in a sleeping bag on the cold floor looking at the peeling turquoise stain on the wall, so sick I couldn’t even stand, I wondered if I’d get medevac’d out, if that was even a possibility in this remote corner of the world.

Already a slim person (at the time), I lost 20 pounds during my three-week experience covering the Kurdish Crisis. I was skin and bones, but I was alive, and truly a new person. It was a watershed moment. Just a few weeks later I gave notice at ABC News in London and planned my new life in Spain as an entrepreneur.

I value and honor what journalism does to shine a light on what occurs in the world, but I yearned to be directly part of changing it, not just recording it. Journalists work hard, often have to put themselves in harm’s way and see more than most people would want to see of the sadness in the world.

I was reminded of this experience last week when I was speaking at a gathering of executive women in Los Angeles. A lovely young Palestinian woman came to talk with me. She was born in the U.S., but her family came from the Middle East. She told me that her parents had fled Kuwait when it was invaded by Iraq. I let her know I had covered the war that resulted from that action. She said, she hadn’t been born yet. Humbling. She was very much like that young Iraqi woman I met all those years ago.

These experiences, and memories, remind me how very fortunate I am to have a home, a family, safety, clean water and food—the basics which so many still don’t have today. And those without the basics are not just across the world, they are in our very own cities and neighborhoods. The needs can feel so big, that we are unsure how to help. I am reminded of Mother Theresa’s quote:

With gratitude and humility,

Barbara Fagan-Smith

CEO, ROI Communication

Chief Catalyst, Living ROI

Subscribe here to get my weekly newsletter directly.

Please forward this email to anyone you think would enjoy it.